In the age of social media, where it feels like there’s a new beauty trend every week, it seems like consumers—especially women—can never keep up. Do I have good facial harmony? Are BBLs even a thing anymore? Should I get Botox? Do I need a skincare routine? Beauty trends have always been fleeting, and looking back into beauty ideals of the past can be a reminder that it’s not you that needs changing—its society.

Source: Art UK and Wikipedia

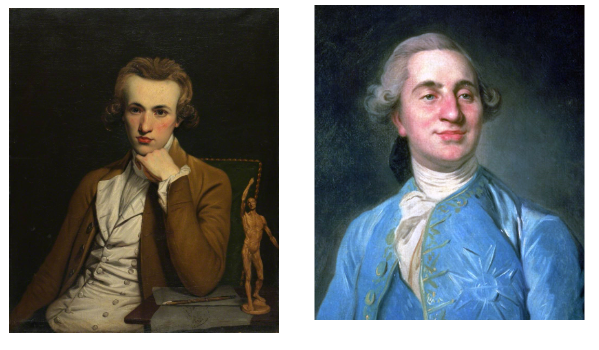

The Dashing 18th Century Man

I’ll set the picture for you. You’re a young, energetic 18th century lady and you’re looking for a handsome man to start a family with. You attend a masquerade and spot him from across the ballroom—with a powdered wig to illustrate his status, white stockings to emphasize his defined calves, and pink rouged lips to indicate his lofty social class—he’s swoon-worthy! That’s right, throughout the 18th century men proudly wore makeup, and you wouldn’t dare leave the house without a properly rouged face. It was considered the pinnacle of masculinity, and no one’s cheeks were brighter than those of King Louis XVI of France himself. The beauty standard at the time was so opposite to ours now that when people call to “bring back manly men” I often wonder if they even know the history they’re referring to. For a huge chunk of history, “manly” men were considerably feminine by modern standards.

The Victorian Era’s Romantic, Full Figure

Right: Portrait of Queen Victoria by Franz Xaver Winterhalter c. 1859

Sources: CNN and Wikipedia

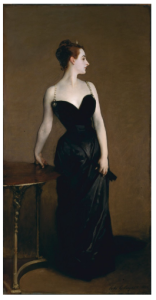

The ideal female figure in the Victorian era—representing living a life of wealth, privilege, and cultured Greek and Roman principles—was full and curvaceous. Weight on a woman’s frame, as reported by the 1908 edition of Physical Culture “fills in the hollows, rounds out, gives the body of a woman the appearance of symmetry.” One of the most famous portraits of the century, John Singer Sargent’s “Madame X,” depicted a woman by the name of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau. She, because of her shapely figure, was described poetically as “a statue of Canova transmuted into flesh and blood.”

The painting originally depicted one strap of the dress falling over Gautreau’s shoulder, but was changed due to social outcry

Source: Wikipedia

The Victorians would be shocked at the slimness of modern celebrities and the contemporary idea that “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels” What was once considered a symbol of utmost femininity and luxury now stands as a stark reminder of how quickly beauty standards can shift and fade.

The “Bee-Stung” Lips of the 1920s

Sources (left to right): Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, EliSoft, Michael G. Ankerich, Starlet Showcase

If you were a young woman in the 1920s you wouldn’t be caught dead overlining your lips. The idea of getting lip filler? Nightmarish. The Roaring Twenties ushered in a fashion revolution, and for the first time in decades, small, doll-like lips were all the rage. Popularized by Hollywood starlets who used layers of grease paint to make their lipstick last under harsh studio lights, “bee-stung” lips were drawn to emphasize the wearer’s cupid bow and—shockingly, to modern standards—deliberately make the lips look tiny.

Source: Sublime Mercies

Hollywood’s original “It Girl” Clara Bow was well known for popularizing the trend, and women all across America sought to replicate the look of her defined cupid’s bow and pouty, heart-shaped lips. The extent of how strange this ideal is to modern standards could not be emphasized more clearly than in how women’s makeup is stylized for films set in the ‘20s. I urge you to open Google, find any movie set in the era, and look to see if the womens’ lips are drawn as small as they should be. From Peaky Blinders to The Great Gatsby—despite being set in the 20s, these shows abandon the bee-stung lip in favor of the modern ideal of full-lipped beauty that has grown so pervasive it overwrites history.