Behind the workings of a turquoise-black prosthetic arm — sized to precision, hand opening and closing, shipped all the way to Portugal — is OHS student Augustine Villalobos (‘23), a high-school engineering enthusiast whose work is fueled by pure empathy. A senior transferring to SOHS in 11th grade, Villalobos has always been interested in innovation — but his work intersects engineering with a sensitivity to those around him.

When asked about motivations, Villalobos said his goal in making prosthetics is to drive “positive change and improve the lives of others through my love for STEM.” With the textbook knowledge in hand, Villalobos creates designs that are not only pieces of tech, but innovations that can be applied to the real-world, real people, and real families.

“I’ve always loved science, engineering, and mathematics. Whether it’s designing prosthetics or researching cures, I’ve realized it’s really what I want to do,” Villalobos says. His experience began even before OHS; he’d been doing similar 3D printing work with the help of his brick & mortar school’s resources.

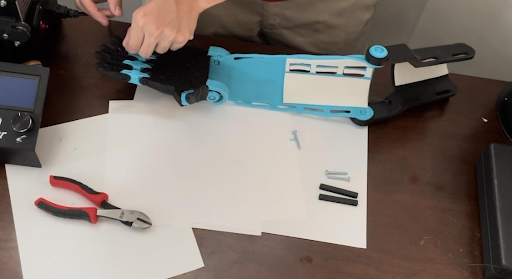

“I was part of my school’s robotics team and I led them to design a prosthetic arm as a project,” he says. “And this device was printed by the school, then later donated to an outreach program for people in need.” When he transferred to Stanford OHS, he looked into the ways he could expand his own horizons of physics and engineering. Most of all, he wanted to continue this prosthetic work, but specifically focusing on a custom prosthetic rather than donating to a larger organization.

And so, Villalobos began working independently — he wouldn’t have the aid of school administration this time, so he needed to create his own funding. “I began tutoring, specifically calculus, to save up for a 3D printer and plastic,” he says. “After that, I wanted to find potential recipients through social media.” He reached out to many, and was faced with a lot of doubts, yet he persisted to find a person in need.

“My first case,” he says, “was when I found a boy named Jesse in Portugal. He was born with a limb difference on his left arm.” With a slight look of remembrance, Villalobos describes how he contacted Jesse through social media and was met with a tinge of natural skepticism, yet the two grew closer and closer throughout their connected experience.

“This was Jesse’s first prosthetic — he’d never operated a left arm or made his left hand close before.” Villalobos asked for right arm measurements, and he used the photos (courtesy of Jesse’s parents) to scale the left-side prosthetic he’d be creating. The design itself, however, didn’t happen all in one prototype — it involved a lot of revision and deliberation.

“Back then in 10th grade, it was school-administered,” Villalobos says. For him, creating this prosthetic by himself was a self-motivated activity, so it took consistent dedication to Jesse’s situation. “After months of designing and production,” he says, “I had finished the arm. but even then, I wasn’t a huge fan of the proportions, so I reprinted, even 6 times for some of the fingers.”

He continues, “I always desired to put in all my effort into something, so when I made this arm, when I saw it wasn’t 100% perfect but it could be. I just knew that I had to keep going and I couldn’t just stop here,” Villalobos says. Throughout the process, he showed a constant reach toward improvement, not just for the 3D model design, but also toward Jesse’s unique situation.

In July, the prosthetic was shipped across the ocean to him. “Everything fit absolutely perfectly, down to the nearest millimeter,” Villalobos says. Reflecting on the experience, he talks about how glad he was that he spent those extra weeks re-designing. “When Jesse sent photos, he would send both arms — the joints completely lined up, the wrists completely lined up, even the fingertips.”

“3D printing can take hours and even days, especially with the components I was making . . . I could’ve just sent it off, imperfect without the revisions, but seeing everything line up . . . you know if you’re really determined, if you strive for perfection, sometimes you can get it,” Villalobos says.

But Villalobos’ words reach beyond the measurements and mathematics — he talks about Jesse and his family, and how they’ve been impacted by the prosthetic. “When Jesse first tried it, he picked up a cup, and I think his mom got a pitcher of water and she poured the water into the cup that he was holding. Immediately he used his other hand under to keep it from falling — but it didn’t fall.” It’s something he’d never experienced before, it was instinctual, and Villalobos’ prosthetic gave something newfound.

“Jesse was just so shocked and so happy, he just really couldn’t believe it. Seeing that video, it just gave me so much joy,” Villalobos says. “It’s something he’s never experienced before.” “It was so meaningful, to see that.”

Villalobos began to realize that he wanted to use engineering not for static creations, but as the instruments of joy in others. “Currently, I’ve just finished making braces for the injured in Ukraine,” he says. “And right now, I’m making two hand prosthetics for a student who’s pursuing a music degree and plays piano.”

Regardless of what’s on the horizon, Villalobos’ values remain steady and true. As a final statement, he says, “In a lot of this prosthetic journey, the key is to just stay determined. There are just times where you can just do anything, and you may experience bumps in the road or roadblocks, but as long as you’re trying your best, you’re persevering.” “You can make such a huge impact by just helping people.”