Black History Month @OHS

February was Black History Month, and several events at OHS both celebrated BHM while also suggesting important ways to eradicate racism. Here’s what Black history is, why it’s important, and what you can do to take part in this movement.

What is Black History? As Kelsey Barnes (’22), president of the OHS Black Student Union, defines it, Black history “is not just looking at all the terrible aspects and everything black people have been through… It’s looking at the joys of our culture…from our black rappers to our black dancers …[And] it’s finding the joy in all of it [and] yet recognizing the terrible aspects of it.”

This exact balance between educational materials on the issues that black communities still face today to a celebration of the joys of black culture is clearly shown through the various events that happened at OHS for Black History Month. Along with a guest speaker event, where Dr. Matthew Clair, Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University, spoke about racial inequality in the criminal justice system, and a Dine & Dialogue with Ms. Alivia Guzman-Shorter, the Director of Diversity and Outreach Programs at OHS, there were also celebratory events such as the fun trivia night “So, You Think You Know Black Culture?” and the guest speaker event featuring members of the Preservation Hall Foundation. Here are the event highlights.

Guest Speaker: Dr. Matthew Clair, Assistant Professor of Sociology @Stanford University

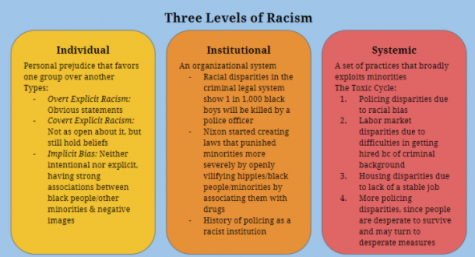

This speaker event covered a variety of topics, from defining race to identifying the three levels of racism, to recognizing and responding to racism. As Dr. Clair explains it, race is a social construct that differentiates people into groups based on their phenotype created during European colonialism to form a basis for assumed superiority, and racism is an ideology of racial inferiority. The three levels of racism, individual, institutional, and systemic, each are harmful to larger society, as shown below.

As Dr. Clair explains, although on the individual level overt racism has decreased, implicit bias is still there and needs to be recognized by everyone. On a broader, institutional or systemic level, however, change must be made not only in the form of symbolic responses such as more representation, but also in the form of policy changes that allow for implicit bias training in the police force, and the abolition of racist laws and practices such as cash bail. Although there is a long road ahead, Dr. Clair ended with the quote “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed without being faced.”

Dine & Dialogue: Dr. Alivia Guzman-Shorter, the Director of Diversity and Outreach Programs @OHS

Dr. Guzman-Shorter, having grown up in a minority-majority region in West Oakland, California, had first-hand witnessed these issues as a child, and when she went to Stanford University for higher studies, she became involved with public health policies as a way to help her community. Her discussion was eye-opening, as she shared statistics that show that racial disparities in the lives of minority communities have not gotten any better since 1970 – it’s actually gotten worse.

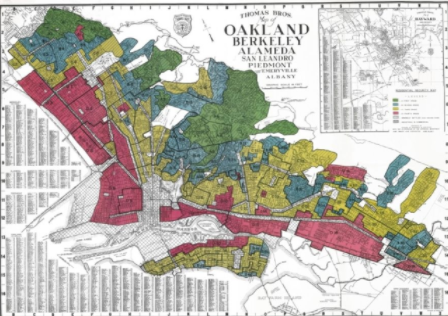

The clearest way to identify the difference in public health for minorities in America is through life expectancy. People in West Oakland can expect to live, on average, 10 years less than those who live in the Berkeley Hills. Why? Dr. Guzman-Shorter goes on to explain redlining, the policy established in the 1930s that has since caused several social determinants in public health.

Redlining is the process where the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), established in the late 1930s and 1940s in preparation for veterans returning from World War II, gave neighborhoods ratings to guide investment. The “red” category was considered the riskiest and was predominantly home to communities of color. This is no accident – the hazardous ratings were usually caused by the racial demographics (primarily black, but any non-white community), with the rubric for these ratings openly stating that race was considered as important a factor as the condition of the property.

These red-lined areas still have an impact today, with the red areas having less food store availability, more air pollution, traffic, congestion, and higher rates of childhood asthma. 87% of San Francisco’s redlined neighborhoods are low-income neighborhoods undergoing gentrification today. And the statistics are only getting worse, with segregation increasing in almost every large suburban area from 1990 to 2000. There’s a clear disparity in the public health resources available to minority, and specifically black, communities, and it’s very clearly linked to zip code and the region where you live.

A Conversation about Music, History, Tradition, and Life

In this more light-hearted event, Ms. Pamela Blackmon and Mr. Calvin Johnson, members of the Preservation Hall Foundation, came to share their stories and promote education, community engagement, and the legacy of music in New Orleans. The Preservation Hall Foundation was established in New Orleans in 1961, and houses the internationally renowned Preservation Hall Jazz Band. Through their organization, they hope to “Protect, Preserve, and Perpetuate” the musical roots of New Orleans. This foundation employs over 50 New Orleans Tradition Bearers, who are people who practice a traditional artistic activity or skill that has been passed on from person to person within a culture, acknowledging and protecting their work with monthly stipends, health care assistance, emergency funds, and more. They also preserve recordings, photographs, and other artifacts from the Preservation Hall’s history, while continuing to chronicle how New Orleans music is evolving today. Finally, they perpetuate their knowledge by reaching over 30,000 students per year, as well as providing free community concerts in public. Although their methods of outreach and education have changed to accommodate for the pandemic, overall the event was a joyous celebration, with several videos bringing the experience of music and dance to the viewers.

Overall, the celebrations of Black History Month at OHS were jubilant, but also educational, bringing awareness to issues still occurring today. Wondering what you can do to help the black community? Check out the below list!

- Be directly democratically involved – Dr. Clair suggests going to town hall/city hall meetings to share your thoughts in open sessions, and bear witness in the court system through court watching, where you can view a case as it is happening and contest any racism that you observe.

- Examine your own personal biases! Through these tests on the Project Implicit website, you can identify the implicit biases within yourself as well.

- Dr. Guzman-Shorter recommends joining youth advisory councils from different medical and governmental associations.

- Kelsey, the BSU president, states that education is the path forward, suggesting that while the OHS curriculum could also incorporate more minority literature, students can always educate themselves through the numerous texts, videos, and podcasts available online. The BSU has also provided this document with resources for allyship.