Conservation Through Storytelling: Michelle Nijhuis’s Field Guide

“We abuse land because we see it as a commodity belonging to us. When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” — Aldo Leopold

Many worry about the future of conservation, but Michelle Nijhuis is equally interested in the past. In her book, Beloved Beasts, she explores the people behind the conservation movement as just that: people. People who tried, and sometimes failed, to save our beloved beasts.

Nijhuis pieces together their stories from handwriting, interviews, and shadows on the wall to create a masterful epic of “humans and other species” in an attempt to make the big questions just a little clearer.

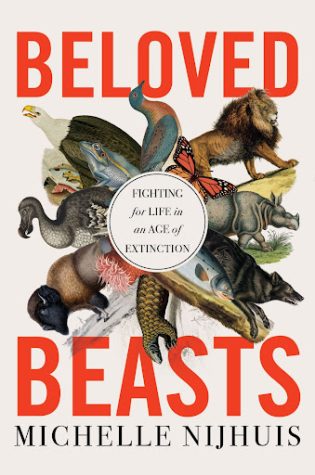

Colorized vintage sketches of irreplaceable species are framed by the vivid and urgent title of Nijhuis’s book. A history of the modern conservation movement that illuminates the past to pave the way for a brighter future, Beloved Beasts will be out in paperback on March 29th.

(W.W. Norton & Company)

How did you go about researching your book?

I spent a lot of time just planning and thinking about who would be the best people to include and not include. I got to work in archives, which was also really fun. It’s great to see the handwriting of someone who has passed away maybe fifty or one hundred years ago. Even though you’ll never get to talk to them, you can read their handwritten letters and start to get a sense of what they were like.

How do you reconcile the often horrible views or intentions of some of these figures with their positive effect on the conservation movement?

It’s very complicated to look back on some of these figures who genuinely did good things for other species but were so clueless in their attitudes towards their own species. I didn’t want to pretend that they were heroes, but I also didn’t want to just cancel them, because I knew that even the people who held really reprehensible views about other people, in some cases, had done important things for other species that we are still learning from today. I think it’s possible to do both—to recognize where people were limited and also to recognize what they did that benefited all of us.

As you delved into this history, what surprised you?

One of the things that struck me as I looked into the history of conservation was that a lot of people who made progress in conservation did it at times that probably didn’t seem very hopeful at all. They probably felt a lot like us. But they went on doing what they were doing because they were passionate about it and they knew that they couldn’t be sure of what the future was going to bring. In a way, their lack of hope gave me hope.

Who do you take inspiration from in your writing?

One of the reasons these people were great conservationists was not just because they were knowledgeable people, but they were very effective in communicating their ideas. People like Aldo Leopold and Rachel Carson wrote a long time ago, but if you read their writing it’s still just so beautiful and so clear. I aspire to that kind of clarity in my work.

What is our responsibility to the conservation movement?

I think that conservation is something that we all need to practice at some level for it to be successful. In that way, it’s helpful for people to know what humans have done before because we can learn from those stories and hopefully build on the good things. There are lots of things that people can do, both on the local level by recognizing what species are living alongside you and figuring out how to support them and by supporting organizations that are working in faraway places. Every day we read things in the news about this or that species going extinct. But there are a lot of wonderful projects out there that are making a big difference. They just aren’t making headlines.

What is the ultimate goal of conservation and science writing?

As science writers, we’re writing about the most complicated—and sometimes the scariest—issues that we deal with as people. “How do we protect life on Earth? How do we protect our own species?” These are huge questions, and I hope that what I do and what other science journalists do is make the questions a little clearer for people.

Michelle Nijhuis will meet with members of the OHS community on Friday, March 4 to discuss science writing. Event details will be shared in Pixel Weekly.