For three years, whenever I practiced tennis on the weekends at my high school courts, I would notice an older man quietly training by himself. He was tall, with white hair, and moved with surprising agility for his age. While waiting for his partners to arrive, he would often hit balls against an old mattress. Sometimes I paused my own practice just to watch him play.

A few weeks ago, I accidentally sent a ball onto his court while he was playing doubles with some friends. One of them waved me over and said, “Hey, you should join us sometime. Do you know Jeff Borowiak? He was a pro—he even played at Wimbledon.”

I was skeptical—I assumed that someone who had competed at Wimbledon would likely be running their own tennis academy or be traveling the world giving interviews, not playing on public courts like any other recreational player. Nonetheless, I thanked them and went back to my drills.

Later that evening, I googled his name, and to my amazement, I discovered that he truly had been a top-20 professional player. Furthermore, he had defeated tennis legends such as Jimmy Connors, Björn Borg, and Arthur Ashe, and had led UCLA as their number-one singles player during one of the program’s most dominant seasons.

The next Sunday, feeling both excited and nervous, I introduced myself and asked if he would be willing to talk about his journey. He smiled warmly and said, “I would be happy to! By the way, I have watched you and your father play—you both play really well.” That friendly response led us to meet the following weekend for a long conversation about his life in tennis.

Borowiak told me he began playing relatively late—he was already a freshman in high school when he first picked up a racket. He spoke with a quiet and thoughtful tone, and he often paused before answering, as if sorting through a lifetime of memories, eager to share the ones that mattered most.

“My first coach was extremely tough on me from day one,” he said. “It was challenging, but it taught me to work hard, stay focused, and believe in myself—values that stayed with me for life.”

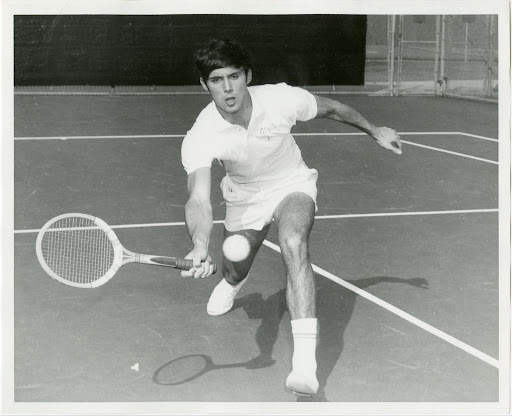

He described the slow and painful process of improvement, recalling hours spent repeating the same groundstroke until it felt automatic. “I was not the most naturally gifted player,” he admitted, chuckling. “But I was persistent. I remember staying hours after games or practices to work on my serves and other parts of my game.” He looked content as he spoke, with a faint smile that showed how much he enjoyed remembering the player he used to be.

By his junior year of high school, Borowiak was performing well in tournaments and caught the attention of college recruiters.”UCLA eventually recruited me,” he said. “And since my ranking was high, turning pro felt like a natural next step. I remember thinking, ‘If you have the level, why not see how far you can go?'”

He shared stories of his time at UCLA, describing the demanding practice schedule. “We would train from eight in the morning until noon, grab a quick lunch, then return to the courts from about three to five in the afternoon,” he recalled. “We still found ways to have fun, though, like heading to the beach after practice.”

He laughed, thinking about all the crazy things he did with the guys on the tennis team. “We were competitive, but also a bit wild sometimes,” he said, grinning. “There were times we stayed up partying all night, and we constantly pulled pranks on each other. That team chemistry made us stronger.” His tone was playful, but there was no mistaking the fondness in his voice—he clearly valued those friendships and the bond they built together.

He smiled when remembering his doubles triumphs with Jimmy Connors. “Winning the intercollegiate doubles title with Jimmy was one of my favorite moments. He brought such fire to the court.”

Borowiak then spoke about some of his most memorable matches. He highlighted a defining moment in 1974 at the North Carolina Tennis Classic, played on clay. He had been seeded eighth and had to face three top-ten players: Dick Stockton, John Newcombe (then ranked number one), and Cliff Richey.

“My game plan was to come in aggressively on almost every second serve,” he said. “It was a bold move, but winning that event proved I could stand alongside the best on tour.”

He leaned back, the excitement in his voice softening. “But even with big wins like that, the hardest battles were often not physical, but mental.”

Mental preparedness, he explained, was the toughest part of his professional career. “Back then, nobody really talked about mental training. You were just expected to tough it out,” he said.

“I started meditating daily using a technique I call ‘cool boredom,’ focusing on a single object for an extended time to remain calm under pressure. Some people, including my wife, thought it was strange that I spent so much time meditating instead of practicing on the court, but it worked for me. It helped me manage anxiety and perform under stress.”

He described how loneliness on the tour could creep in, especially when traveling for months at a time. “There was pressure to always perform, and not much room to talk about how you felt. You kept things bottled up. That took a toll.”

Borowiak’s expression grew more serious. He spoke more slowly now, and it felt like he was remembering some difficult moments. You could tell tennis had given him a lot—but it had also tested him. “Learning to ground myself mentally was probably the most important skill I developed. It kept me sane.”

He paused for a moment, as if debating whether to share what came next.

“There was one time that really tested everything I had learned,” he said, his tone shifting again. “It was during a tournament in Lagos, Nigeria.”

The event Borowiak was referring to was the 1976 Lagos Tennis Classic, a regular stop on the pro circuit that featured many of the world’s top players. He was set to face fellow American Arthur Ashe in the semifinal match—a highly anticipated showdown between two strong competitors. The tournament had been progressing normally, despite the underlying tension in Nigeria, where political unrest had been brewing for months. At the time, Nigeria was facing political instability, but few expected anything to unfold during the matches. For Borowiak and the others, it started out as just another stop on a demanding travel schedule—until everything changed.

Borowiak took a deep breath before continuing. “It was like a scene from an action movie. Soldiers with machine guns suddenly marched onto the court, ordering everyone to leave. We soon realized there was a coup going on. Arthur and I were rushed out of the stadium, along with the U.S. ambassador. We had to navigate streets lined with soldiers to get to the airport—at one point we abandoned our car and continued on foot. Eventually, we caught a flight out of Lagos. It was surreal—one moment I am returning Arthur Ashe’s serve; the next, I am running for my life.” He and Ashe escaped through the chaos-filled streets alongside the U.S. ambassador and the soccer legend Pelé.

As he recounted the story, he looked a bit uneasy, like the memory still lingered with him after all these years.

“You train for years to control what happens inside the lines,” he said firmly, “but that day reminded me how little control we really have outside of them.”

It was a moment that, in his words, changed his perspective on pressure. “After that,” he added, “losing a match never felt quite as serious.”

Thinking back on that experience seemed to give new context to everything Borowiak had shared—his discipline, his mental toughness, and even the way he still enjoyed playing today. Whether in a high-stakes match or an unexpected situation off the court, he had learned to stay composed and adjust as needed.

For high school students hoping to play college or professional tennis, Borowiak offered clear advice. “Train with a real purpose. Do not just show up to practice; have a specific goal in mind each time, like improving your serve or working on your footwork. Embrace the drills you struggle most in because that is where you will grow the most.”

“Also, do not neglect the mental side of the game. It does not have to be meditation, but find something that helps you deal with pressure. And most importantly, keep tennis fun—if you love it, you will stay motivated.”

In my conversation with Borowiak, he reminded me that, in tennis and in life, it is not only about winning titles—it is about staying committed, staying curious, and never losing the joy that first drew you to the sport.

Peter Lerner • May 29, 2025 at 7:25 am

This is a beautifully written article. I’ve been playing tennis for decades, often with someone was on the tour with Borowiak in the 1970s, Steve Turner, and at Turner’s suggestion, I flew to Seattle to take a few lessons with Jeff. They were the most memorable lessons of my life … and it started in his apartment, in which I hit against a mattress that was leaned up against a wall. Borowiak also made me about the best cup of coffee I ever had, and played a mean piano keyboard. I’d love to visit with him again. Can you ask him to contact me? Peter