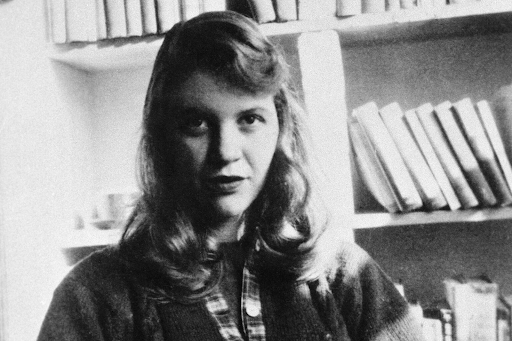

A few years ago, I remember being wrapped up in a fluffy blanket, my nose in a copy of The Bell Jar, looking into the frayed pages like they were a mirror. Written by the notoriously turbulent writer Sylvia Plath, the novel follows Esther Greenwood, a poet descending into psychosis, all while she lives within a 1950s-American version of womanhood.

And yet, despite Plath’s incisive body of work, including her thinly-veiled autobiography, she’s still massively misunderstood; her untimely suicide is all too often romanticized as tragic beauty, the tale of a broken literary genius. In 2023, we criticize 50s’ notions on womanhood, but we find that life still imitates art. Just like how Plath’s writing was iconized into female sadness, the way we perceive media reflects larger issues of romanticization.

Among Instagram filters, cancel culture, and microtrends, one thing resonating from Plath’s time is a depiction of mental illness — in particular, a modern movement that began with de-stigmatization and now errs on the side of glamorized insanity. And in an online school, many students are in-tune with how social media, especially its depictions of mental health, impact us as consumers of it.

Zoe Schurman, an OHS senior this year, brings to light early pandemic trends online, with a focus on aestheticizing small moments in life. She says, “this huge push to romanticize one’s life . . . it’s really cool, the little things bring a lot of joy to mine.” “But I think that when people with mental illness romanticize their life, it can get really complicated.”

She cites Pro-Ana as an example of this, where young people with eating disorders form self-enabling communities, ones that only worsen their condition. “It’s especially true as a social contagion . . . it can cause people to have really messed-up understandings of what things actually are,” Schurman says.

Offering an athlete’s perspective, competitive gymnast Allie Forbes gives her own take on this subject. “Being in a sport where dieting/eating is a big issue, personally I’m lucky to not have experienced too much of that, but I’ve heard stories from my coaches and other people about the whole romanticization of dieting and body shape,” she says. For context, gymnastics is a sport in which disordered eating — experienced by 28% of young women at the elite level — is strikingly prevalent.

In Forbes’ words: “This sort of mindset is 100% contagious. It’s because people are led to believe that these conditions are desirable or fashionable and then are influenced to adopt these attitudes.” Many people start the sport at a young age, and knowing how children learn by mimicry, there’s an almost generational line of gymnasts who struggle with disordered eating habits.

There’s certainly an appearance aspect too, knowing how Forbes framed conditions being “fashionable” in a way. OHS Junior Charlotte Own offers her own perspective, taking into account how when there’s “a pretty girl talking about her experience with depression/anxiety, her post is likely going to get a lot more eyes on it than that of a less pretty girl.” Pretty privilege and romanticized mental illness go hand-in-hand.

Own elaborates, “I’ve seen so much of like ‘crazy girls are the prettiest.’” She references a fashion style in Japan that revolves around this kind of rhetoric: “Jirai Kei, on the surface just looks like a cutesy, Lolita-adjacent J-fashion, but it’s very tied to this aesthetic of self-harm and girls-gone-crazy which is very weird to me.”

Known for its themes of femininity and mystique, it’s one of the most popular alternative styles of fashion in Japan right now. “I go to Shibuya and see a ton of girls wearing it — even I have a decent amount of Jirai Kei clothing,” she says.

A lot of these discussions have a specific focus on women’s struggles with romanticization, and OHS 9th grader R.J. brings up a larger conversation about gender dynamics when it comes to this. “When a woman is struggling with depression, she’s often depicted as beautiful and frail — even in literature written by women, it’s romanticized. But when the same thing is happening to a man, they depict him as fat and pathetic, and that’s often pretty telling.”

Much of this ties back into the concept of life imitating art: our own struggles reflect the content we consume. R.J. says, “I was going through a rough patch, and I honestly could not stop romanticizing it . . . all I could think about was those thin, pretty, starving girls so often depicted in media. Sitting around in slip dresses, smoking and laying in bed beautifully.”

She says that “for women, pulling ourselves out of depressive episodes is so difficult because society tells us our tragic beauty is what gives us worth.” In her words, the growing glamorization of mental illness is what “enforces a culture of complacency,” when the ultimate goal should be “recovery or at least acceptance.”

Perhaps we’re living in an Esther-Greenwood, Bell Jar world, where all our tragedy is viewed through rose-tinted glasses. Perhaps our culture is to blame here, a culture that tries to gouge beauty from every crevice, even when the goal should be to heal, not to glamorize. But still, there’s no denying that the media directly influences how we behave, whether it’s in diet culture in gymnastics, the fashion styles in Japan, or societal gazes on women.

In a brief yet poignant few words, OHS freshman Zara Khanna may express what we’re all feeling: “Mental health is not a media trend or a passing concern — it’s a real thing that affects real people. Romanticizing the struggle of other people fighting a very real fight is not and never will be okay.”

I’d say it’s high time for a shift in the culture we’ve created.