“If we make it to shore, he says, I will name our son after this water. I will learn to love a monster. He smiles—a white hyphen where his lips should be.”

In Ocean Vuong’s Night Sky with Exit Wounds, even survival bends toward poetry. Here, a father’s fragile promise folds itself into the cadence of the sea, love buoyed by the weight of its own impossibility. In lines like these, Vuong does not merely depict the immigrant experience—he transmutes it, transforming memory and loss into something luminous and sharp-edged, a sea glass held to light.

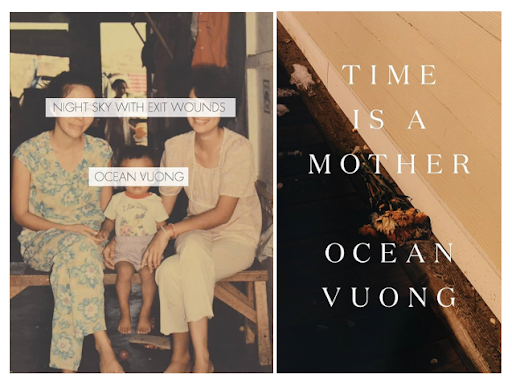

Much has been written about Vuong as the literary wunderkind who, with a single collection, redrew the boundaries of American poetry. But Night Sky with Exit Wounds is more than a debut; it is’s excavation of belonging, an autopsy of inherited grief, a map drawn in reverse. These poems refuse the flattening impulse of “trauma narratives” or the sentimental trappings of immigrant mythos. Vuong, instead, crafts a poetics of rupture, where the past is a splinter that won’t come loose and language is both scalpel and salve.

Born on a rice farm in Saigon, Vuong’s own trajectory reads like the stuff of American folklore. He was two when his family arrived in Connecticut as refugees, carrying just three letters of English—A, B, and C—learned from a neighbor in a Vietnamese camp. Those letters, taught to Vuong’s mother, would form the scaffolding for a new lexicon: “a b c a b c,” Vuong recalls in “The Gift,” his mother’s voice a hymn to the unknown. What Vuong builds on that foundation, though, is wholly his own—words as luminous as they are devastating, flares in the dark.

In “Aubade with Burning City,” Vuong collapses history and magical realism into a single, haunting fugue. April 29, 1975: Armed Forces Radio plays Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas,” a signal for Americans to evacuate Saigon. Vuong’s poem interlaces Berlin’s lyrics with chaotic images of war, a counterpoint that crescendos into silence. “A helicopter lifts the living just out of reach,” he writes, each line jagged as broken glass. The space between stanzas feels like the pause before a door slams shut. This is Vuong’s genius—history becomes something you can hear, and silence becomes part of the story.

Vuong’s work insists on this simultaneity of beauty and violence, the way one is often inextricable from the other. His poems operate as double exposures, layering the personal and the historical until they blur. In “Into the Breach,” Vuong writes, “To love / another man / is to leave no one behind.” The line unfolds like a confession but lands like a manifesto, as expansive as it is intimate, love becomes both transgressive and close.

It’s no wonder Vuong has become a touchstone for young poets. In high school literary contests, his style in “Someday I’ll Love Ocean Vuong” is as mimicked as it is revered. Take Fiona Jin’s striking contrapuntal poem, “someday I’ll throw fiona jin off a building,” a homage that reflects Vuong’s influence on a generation unafraid to wrestle with selfhood in all its multiplicity. Jin’s poem, like Vuong’s, doesn’t ask for permission—it takes up space and remakes it.

Yet Vuong himself resists becoming a fixture, preferring movement to monument. His follow-up collection, Time Is a Mother, shifts inward, exploring the grief of losing his mother with a quieter, elegiac tone. In “Amazon History of a Nail Salon Worker,” Vuong turns a shopping list into an altar, each item—a pain relief patch, a birthday card—steeped in the ache of absence.

Now, as Vuong prepares to release his second novel, The Emperor of Gladness, in 2025, the literary world waits for his next act. But Vuong doesn’t seem interested in “arrival”—he is more interested in the act of becoming, the infinite journey of language itself.

For Vuong, the immigrant story is not just survival; it is the refusal to vanish. To name the monster and learn to love it. To hold on to what slips through.