On the Outskirts of an Epic: Why We Are drawn to Madeline Miller’s Vivid Reimaginings of Ancient Myths

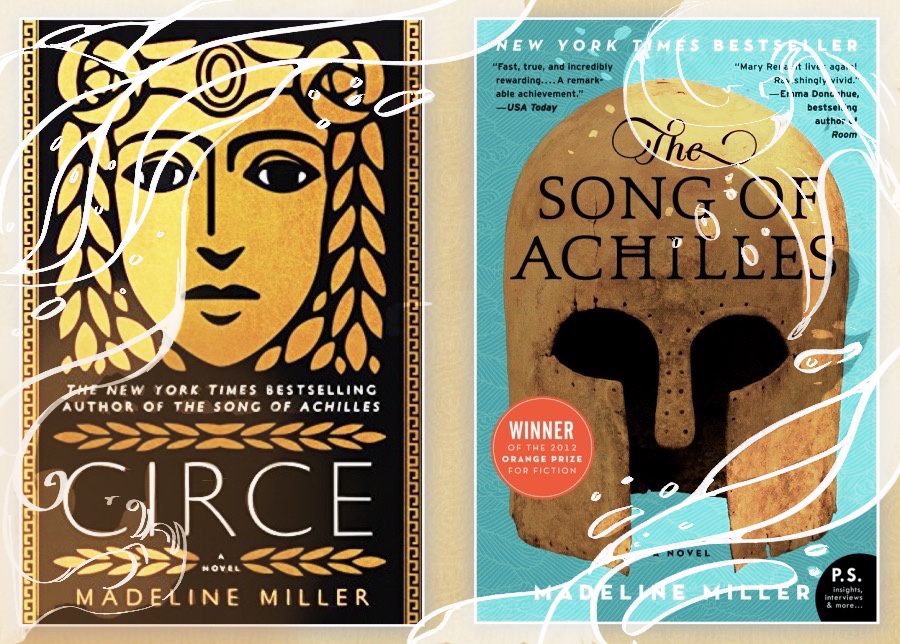

Back Bay Books (L) and Ecco Publishers (R)

Madeline Miller’s two books side by side—contrasting colors but similar silhouettes.

“Rage—goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles, / Murderous, doomed, that cost the Achaeans countless losses, / hurling down to the House of Death so many sturdy souls.”

So go the first lines of the Iliad, an ode to rage far more than a tale of Achilles.

Unlike the epics of old, Madeline Miller’s mythological retellings evoke no muse. With piercing first-person prose, Circe and The Song of Achilles watch the events of the Iliad and the Odyssey unfold from the outside.

Why are we still so drawn to these ancient tales in the modern era? What is it about Miller’s vivid reimaginings that brings them to life?

As a classicist who has taught Latin, Greek, and Shakespeare to high school students for over fifteen years, Miller is deeply familiar with Greek mythology. We all know about Achilles and Odysseus, but perhaps not their friends, helpers, and lovers, which frees us from our preconceptions. These side characters come alive in the gaps of their stories.

The immortal witch, Circe, is isolated on the island of Aeaea, as her power threatens the gods. In the opening of her story, Circe tells us that “when I was born, the word for what I was did not exist.” Pieced together from various texts, Circe creates a new myth. It is a story of solitude and power, humanity and immortality. Most of all, it is the story of a life that is all too often glossed over.

In the original mythology, Circe is defined by her interactions with others. During The Odyssey, she notoriously turns Odysseus’ men into pigs when his crew washes up on her island—though her motive is left ambiguous. After convincing from the silver-tongued Odysseus she returns them to their human forms and harbors them for over a year. When Medea and Jason flee to Aeaea with the golden fleece and blood on their hands, Circe cleanses their souls. Circe is commonly portrayed as the evil sorceress or beguiling enchantress in other stories but has never been the hero of her own.

Miller’s book came at the perfect time. A couple of years after its publication, the world went into lockdown. We were all stranded on Aeaea. With Miller’s story, we would at least have Circe for company.

The Song of Achilles, on the other hand, is not a story of isolation but of love. It is not told by the infamous Achilles, Aristos Achaion, best of the Greeks, but by his closest friend and lover, Patroclus. Achilles and Patroclus come as a set. They are inseparable. “He is half of my soul, as the poets say.”

Patroclus is, in many ways, defined by Achilles. He is an exiled prince with no particular skill in battle or heroic destiny. Instead, Patroclus must fight to stay by Achilles’ side, in life and after death. He battles the tightening threads of fate, Achilles’ nymph mother who wishes godhood for her child, and the hardening of war. Most of all, he battles obscurity.

Where Circe wanders through her immortality, Patroclus is all too aware of Achilles’ impending doom. The hero was prophesied to live a long but forgotten life, or fight in the Trojan war only to die young but glorious, going down in history.

Much of the book is about Patroclus and Achilles’ youth. They play in the water, eat figs, and train with Chiron on Mount Pelion. Yet, the reader’s knowledge that Achilles will die hangs over every bright moment. The Song of Achilles keeps all of the same players and plot points of the Iliad, but derives brilliance from this tonal shift.

More than that, it illuminates the romance between Achilles and Patroclus in a way that few other adaptations have. In the original text, Achilles describes Patroclus as “the man I loved beyond all other comrades, loved as my own life.” But, for instance, in the 2004 movie Troy, they are cousins, and this deep connection is explained away by blood relations.

Circe and Patroclus are both outsiders in their own stories. They do not see themselves as heroes, or even main characters. They do not expect the world to care about them.

We may not see ourselves in the heroes of old, beloved by the gods and defined by their superhuman abilities. Yet we can understand Circe and Patroclus, who falter and fail and who are forgotten and silenced. Miller assures us that their stories still matter. Everyone’s story matters.

They need no muse other than Miller.