Politics of the Qatar World Cup: Getting Into Football (Part I of IV)

FIFA President Giovanni Infantino and Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani hand the World Cup to Lionel Messi and champions Argentina.

The FIFA World Cup 2022 in Qatar has been widely criticized for human rights abuses, corruption, environmental concerns, and more. Qatar’s world cup is a product of global political, military, economic, and technological currents, with roots as deep in the past as the mid 1800s. The Qatar World Cup has its roots in war, corruption, and revolution, and its geopolitical implications reach far beyond the middle east. In this series, we will take a deep dive into the politics behind the tournament, as well as the behind-the scenes of the selection for the host of the World Cup, how it was set up, and what affected how it was publicized, especially by nations outside Qatar. In this part, I’ll talk about what led to Qatar’s interest in football as a means of capitalization. There are three important dates in 1990 that led to Qatar’s fateful 2010 bid.

First, let’s consider January 19th, 1990, when the Taylor Report, also known as The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster Inquiry, was released. This was an investigation by Lord Justice Taylor into a fatal crowd crush in a stadium that killed 97 Liverpool fans.

This report blamed poor policing for the disaster, and it was not until over 20 years later that the English government took responsibility. However, the immediate effect of the report was a change in stadium infrastructure; it highlighted how crumbling Victorian stadiums (which consisted of a large number of stadiums in England at the time) were unsafe. It also recommended that standing terraces (i.e. inclined terraces for spectators without seats) be banned; this led to all-seater stadiums to be introduced. Without this reform, it would have been impossible to form the Premier League two days after. Within a decade, the EPL became one of the most watched and profitable sports leagues in the world. It was formed in the image of Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister whose economic reforms created an unequal and unregulated economy. The wealthy thrived while those below suffered. The super-rich around the world saw in the EPL an opportunity to invest and further their wealth. Even nation states began to look at football as a viable political tool.

Let’s move to February 7th, 1990, in Moscow, the day the general secretary of the communist party of the soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, recommended that they give up their monopoly on political power. Within weeks, the Baltic states held their first ever competitive elections. On March 11th, the Act of the Re-Establishment of the State of Lithuania was passed, and thus the country claimed its independence from the Soviet Union. Other territories within the USSR soon followed. In August 1991, hardliners launched a coup against Gorbachev, who instead were faced by thousands of Muscovites who took to the streets in protest, among them Boris Yeltsin.

He was famously filmed riding a tank. The coup failed. By the end of the year, the Soviet Union had fallen. Yeltsin was now president of a newly independent Russia, in a new world with a new democracy and new market economy. Many found profit in oil. The fall of the Berlin Wall brought freedom to millions, but also handed the opportunity to a group of businessmen to take advantage of the chaos to make fortunes in an opaque way. This brought rise to the oligarchs, who became millionaires, then billionaires, as Yeltsin handed them state-owned companies in oil, gas, and metals to make sure he could stay in power. Among these oligarchs was a rubber duck salesman named Roman Arkardyovich Abramovich, who saw football as a way to benefit from this new class of super-rich.

A year earlier, on August 2nd, 1990, in yet another part of the world, Iraq invaded Kuwait. Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s ruler, had been leading a war of expansion against neighboring Iran. The United States had been supporting Iraq because Iran was a common enemy. The war took a million lives and almost bankrupted the country. The neighboring Kuwait had bankrolled Iraq and wanted its billions of dollars in loans repaid. To make matters worse, the price of a barrel of oil had collapsed from $40 in 1981 to $12 in 1988. Almost all of Iraq’s foreign reserves came from oil sales. Iraq baselessly claimed that Kuwait was stealing Iraqi oil by drilling across the border as grounds to invade and occupy Kuwait, claiming it as an Iraqi province and fleeing the debt. The Kuwaiti emir managed to flee to Saudi Arabia, but the remaining elites were rounded up, jailed, tortured, and murdered. Sheikh Fahad al Ahmed al Jaber al Sabah, brother to the king, was killed while defending the Dasman Palace. His body was laid on the steps of the balance and crushed by an Iraqi tank as a warning. Sheikh Fahd had become famous during the 1982 World Cup finals for entering the field during France vs. Kuwait, trying to persuade the referee to disallow a French goal. Saddam believed western nations were in decline and the US would not commit ground troops to prevent the Kuwaiti invasion, but the 1990 oil collapse and the invasion piqued George H. W. Bush’s interest. An international coalition was built including Arab nations, fearing Saddam. Saddam, hoping to create “the mother of all wars” (which he calculated Iraq would win), ordered a new provocation after the US started attacking Iraqi positions in Kuwait. Iraq invaded Saudi Arabia and captured the port of Al Khafji. Coalition forces were forced to engage. Leading the charge were two tank companies from Qatar, rolling into Al Khafji under the command of Qatari crown prince Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani.

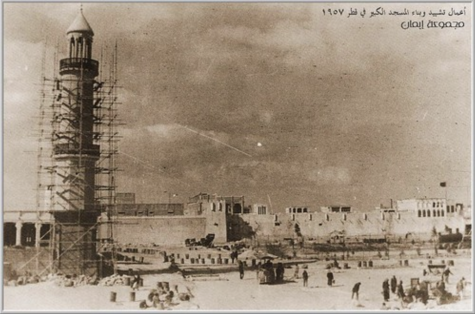

This brings us to Qatar. Its history has been molded by its position between larger competing powers. It built a reputation for mediation and negotiation. The Al-Thani family had relatively recently acquired power in the gulf, taking control in the mid-19th century after signing an agreement with the British that recognized their claim over the whole Qatari peninsula. In 1871, Qatar came under pressure to accept the rule of the Ottoman empire. When the Ottoman empire collapsed after WWI and retreated to Qatar, the British empire took its place in 1916. The Al Saud had been a continued threat on the southern border of Qatar, especially once oil had been discovered in the region; Britain would provide protection. Back then, Qatar was a poor pearling and fishing backwater, one British civil servant describing Doha as “little more than a miserable fishing village straggling along the coast for several miles and more than half in ruins.”

People had to fetch their water in skins from wells two or three miles outside of the town. When oil was found in Qatar in 1939 during a period of extreme poverty referred to as “the years of hunger”, the population of Qatar was only 16,000. Crude oil was not exported until 1959, and life was still precarious. In 1960, a quarter of Qatari women still died in childbirth. But oil was now flowing and Qatar was on its way to becoming a wealthy power, and soon an independent nation. British prime minister Harold Wilon announced in 1967 that Britain, not being able to afford colonialism anymore, would be retreating from its military bases east of Suez. The British had long provided protection to Qatar and the Al-Thani’s, along with Bahrain and the other so-called “trucial states”, including 7 tribal families who eventually formed the United Arab Emirates. In 1971, shortly before the UAE’s seven emirates united, Qatar announced its independence. A year later, Sheikh Khalifa bin Hamad Al-Thani seized power from his brother, Ahmed bin Ali (after whom one of the new World Cup stadiums was named), while he was on a hunting trip in Iran. Sheikh Khalifa built a modern state using money received from oil. The oil soon ran out. In 1971, Shell discovered the “North Field,” the largest deposit of gas in the world. In 1977, Sheikh Khalifa named his son, then Major General Hamad, crown prince. The oil price collapse of the ‘80s had a ruinous effect on the finances of the gulf countries.

In 1990, as you’ll recall, Saddam invaded Kuwait. It was important for the Saudis that Arab forces led the fightback (instead of non-Muslim forces such as the Americans). It was under Sheikh Hamad’s command that the Qatari tanks were one of the first to engage Iraqi troops, the first time the Qatari troops had ever been engaged in any armed conflict. Saddam’s troops retreated, and Sheikh Hamad was hailed as a war hero. He had power and reputation as a warrior crown prince, and had virtual control of the country while his father spent his time in Switzerland. In 1995, Sheikh Hamad led a successful bloodless coup against his father at the palace. Most Qatari tribes gave their oath of allegiance to him, although not everyone was happy. A counter coup was launched in 1996 but the Bedouin tribes paying to cross the border from Saudi Arabia got lost in the desert, and so did a boat of French mercenaries, led by Sheikh Khalifa’s former bodyguard. There were later accusations that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) was behind the plot. Sheikh Hamad was seen as a reformer. According to an Economist article in 1996, the royal families of surrounding Gulf states were worried about this behavior. The ministry of information was abolished, and the Al Jazeera news network was established. FIFA announced that they would make democratic reforms and have an elected advisory chamber. Women would have the vote. Hamad talked of a British-style constitutional monarchy where the Emir was the head of state but the power resided in an elected parliament. The exploitation of Qatar’s gas wealth changed everything — it suddenly made Qatar the richest country in the world (per capita). Qatar had historically negotiated and mediated to stay in power in a space between greater, covetous powers, and these skills gained it protection from the United States. The First Gulf War had only solidified Qatar’s position. Fortunately for Qatar, the Americans could not set military bases in Saudi Arabia due to hostile local opposition. Emir Hamad found a solution; in 1996, Qatar spent over a billion dollars building the Al Udeid air base and invited the U.S. to stay. After 9/11, the U.S. military moved its regional command center, CENTCOM, to Al Udeid. Just like the British in 1916, the U.S. would now be the ultimate guarantor for Qatar’s safety.

By the turn of the 21st century, Qatar had been revolutionized into one of the world’s richest countries and a regional powerhouse from an impoverished colonial backwater. Those seemingly unrelated events — the Hillsborough formation of the EPL, the collapse of the USSR, and the invasion of Kuwait — had all laid the foundations for Qatar’s next spectacular act: pushing the country’s brand. Instead of investing into expensive advertising campaigns, they allowed sport to promote their country’s brand instead.

The Qatari had been making efforts to become a soccer powerhouse. Take, for example, Brazilian striker Ailton Goncalves. He signed for Werder Bremen in 1998. He was powerful, charismatic, and prone to madcap flourishes. Because of his large frame and surprising pace, he was nicknamed Kugelblitz — the German name for ball lightning, a.k.a. St Elmo’s fire. Ailton had an interesting personality. He would spend thousands every month on clothing. Some days, he would play like the best forward in the world, and the next day he would not even show up to training. But in 2003, it all came together. The Ball of Lightning was taking the Bundesliga by storm. By 2004 he had scored 28 Bundesliga goals and won the league and cup double for Werder. Big European clubs started to take notice. Despite being one of the world’s deadliest attackers, Ailton was ignored by the Brazilian FA and was never called up for the national team. In March 2004, Ailton arrived in Doha after receiving an intriguing proposal from the Qatari royal family: they wanted him to join their national team. Qatar, as did many smaller nations in the early 2000’s, utilized naturalizations to make their national team competitive. Despite having got to within one goal of qualifying for both the FIFA World Cup 1990 and 1998, Qatar had never qualified for a World Cup. According to Qatar national team head coach Philippe Troussier, a Frenchman, naturalization was probably the only means to one lday qualify Qatar for a world cup. “Naturalizations are nothing new to Qatar, 80 percent of my squad were not born in Qatar,” said Troussier. The nation had already spent large sums to attract big stars at the end of their careers to come to Qatar and play in the Q-League, raising the standard of the players around them — Marcel Desailly, the De Boer brothers, Pep Guardiola, and Gabriel Batistuta, just to name a few. Wealthy countries with less footballing prowess attracting large players is still very prevalent, with the legendary Cristiano Ronaldo recently signing for Al Nassr in fellow gulf country Saudi Arabia. Despite the league efforts, Qatar’s national team did not improve. Qatar thus used another tactic; Ailton was offered a million dollars up front and nearly half a million a year to play for the Qatari national team and help them qualify for the 2006 World Cup. “Brazil does not want me. Germany is not prepared to take me. That’s why I have decided to play for Qatar, which appreciates me. I want to fulfill my dream to play for a national team,” announced Ailton. Unfortunately for him, this dream never happened. FIFA was appalled that a transfer system of international players was being set up by Qatar. FIFA president Sepp Blatter was furious and said that stopping Ailton’s move was a top priority for him. “It is against the spirit of the game … and FIFA will aim at curbing this practice.” Qatar had pushed the rules to breaking point. FIFA banned the practice, a hugely embarrassing moment for Qatar.

Two months later Emir Hamad signed “Law No. 16 Establishing the Academy of Sports Excellence (Aspire)” to “achieve Qatar’s ambitions in sports competitions regionally and globally.” Within 18 months a state of the art sports facility was built, and Pele and Maradona, then considered the two best players of all time, were galavanting on stage together. Aspire embarked on a campaign to scout every single potential young player in Qatar, visiting every school and holding trials for Qatari kids as young as six. Not content with that, they launched “Football Dreams,” a $100 million scouting project looking for the most promising children around the world. Over a seven year period 3.5 million young boys were screened; just 20 would be offered a full scholarship each year. Football Dreams was highly controversial; critics accused Qatar of plundering African regional talent and taking it to Qatar in hope of circumventing the tough new naturalization laws that Qatar’s behavior had prompted. Qatar denied the accusations, claiming Football Dreams was a humanitarian project, and that nobody would be compelled to represent Qatar. It did mark a brand new, strategic policy direction for Qatar; one where sport and football would become part of government policy and part of the nation building process.

The UAE, especially Dubai, had been particularly successful in leveraging sport to advertise itself to the world. Dubai was one of the UAE’s seven ruling emirates, with Abu Dhabi as the seat of power. From the 1990s, under the effective rule of its young ruler Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al Maktoum (who oversaw Dubai’s remarkable transformation while his shy brother Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid al Maktoum was technically in charge until his death in 2006), Dubai focused on trade. It marketed itself to a global audience as a luxurious place to live, buy property and take vacation. It was a necessary economic move. Abu Dhabi had most of the oil — 95% of the UAE’s oil reserves, making up 7-9% of the entire world’s oil reserves — and also the real power. Dubai’s reserves were tiny in comparison and would soon run out. By 2006, just 6% of Dubai’s economy was dependent on hydrocarbons. Dubai, like Qatar, had to prepare for a post-hydrocarbon world and had achieved incredible international exposure with the help of sport. They hosted the Dubai World Cup, the world’s most expensive horse race; they hosted a PGA tour event where Tiger Woods regularly appeared; and the Dubai Tennis Championship, where Roger Federer regularly won the title. Dubai’s name, and that of state owned companies like Emirates Airlines, started appearing on football shirts and on football grounds in Europe, with some of the largest teams such as Chelsea, Arsenal, Paris Saint-Germain, Real Madrid, Benfica, and AC Milan boasting “Fly Emirates” on the front of their jerseys. Emirates Airlines was a major sponsor of FIFA and the World Cup, as well as the world’s oldest competition, the English FA Cup. Emirates paid almost half a billion dollars, which is worth almost a billion today, to secure the naming rights of Arsenal’s stadium until 2028. In 2007, it went a step further when Sheikh Mohammed, a man who loved horse racing and had spent millions building the Godolphin racing stables in Newmarket, attempted to purchase Liverpool, using a sovereign investment vehicle, Dubai Investment Capital. Remember Roman Abramovich, the rubber duck salesman and Russian Oligarch? He went on to buy Chelsea, changing the game. The huge amounts of money spent transforming Chelsea into champions (with little regard for profit or loss) had never been seen before. The EPL, as well as the UEFA Champions League, attracted businessmen from America, Asia, the Middle East, and beyond to the global popularity of soccer. Furthermore, the booming TV rights deals continued to increase in value. They saw soccer as the biggest and most effective advertising real estate in the world, whether you were selling shoes, tourism, or a new vision of your country. Buying Liverpool would be the biggest coup yet. But it never happened. The club instead turned to two American billionaires, Tom Hicks and George Gillett, who had a brief but disastrous ownership of the club before being forced out. Still, thanks in no small part to celebrity sporting endorsements, Dubai had put itself on the map.

Qatar followed suit with its own tennis championship Qatar Open and golf tournament, and, most importantly, its football league. Qatar even managed to win the bid to host the 2006 Asian Games, the smallest country ever to do so. Qatar wanted something bigger — a World Cup, perhaps, or maybe the Olympics — but the heat of the desert seemed to make it impossible. Much of the investment failed. Qatar didn’t qualify for the 2006 nor the 2010 World Cup. The 2006 Asian Games were a disaster after rain caused hazardous conditions. Several fans were killed in car accidents on their way to an event, while a South Korean jockey was killed when his horse slipped in the mud. A prison ship had to be brought in to house some of the competitors due to a hotel shortage. The Q-League had also declined in popularity, and big names were no longer coming to play. After proposing its plans to host the 2016 summer Olympics in Doha, which they proposed could be moved to the cooler month of October, the city did not even make the shortlist when it was announced. Qatar also failed to become a candidate for the 2020 Olympics.

In 2008, the world was having an economic collapse triggered by toxic mortgages in the U.S. When it hit, and asset prices tumbled globally, Dubai was hugely exposed. The emirate had largely relied on estate and debt, while Abu Dhabi had the actual money from years of high oil prices. The UAE president, Sheikh Khalifa, convened a meeting between Dubai’s Sheikh Mohammed and crown prince Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed. A 10 billion dollar bailout was agreed. This was humiliating for Dubai. In return, Sheikh Mohammed agreed to name the tallest building in the world, Burj Dubai, after Sheikh Khalifa, thus giving us the Burj Khalifa. Abu Dhabi, meanwhile, went on a spending spree. In August 2008 Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed al Nahyan, the UAE’s deputy prime minister and brother of crown prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, announced that he was buying Manchester City. A few days later, City finalized the purchase of Brazilian Robinho for a then-staggering $60 million, just before the transfer window shut. When it opened again in 2009, the club spent another $90 million. In 2011, City made the largest single season loss in the history of English football, about $350 million, but also achieved phenomenal success on the pitch, while wearing shirts labeled with and a stadium named after Etihad Airways. Abu Dhabi would no longer be in the shadow of Dubai. Although Sheikh Mansour has always claimed City was a personal project and not a state-owned club, it was still as transformational as Abramovich’s purchase in 2003. The people brought in to run Manchester City were the same that ran Abu Dhabi’s political affairs and its multi-billion dollar investment vehicles. Now, football clubs were a matter of state. Football was about to begin the sovereign age; one that Qatar was soon to join.