The United States Dollar has been the dominant currency of the world for the past 80 years. It is used in 88% of foreign exchange transactions and takes up 59% of all foreign exchange reserves, making it by far the most widely used currency in the world. Over the past couple decades, however, the dollar has shown signs of weakness and regression. This phenomenon is called de-dollarization, which notes various countries’ attempts to move away from the dollar being the world’s chief reserve currency.

To understand why de-dollarization is occurring, it is important to first outline how the dollar rose to power. Before it entered World War II, the United States was the main supplier of weapons and resources to Allied countries. They mostly paid in gold, resulting in the U.S. owning most of the world’s gold reserves by the end of the war. A return to the global gold standard was therefore impossible as countries had depleted their reserves.

Seeking a stable economic system in the wake of the war, 44 countries signed what’s known as the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1944. Besides marking the creation of the IMF and the World Bank, it created a fixed exchange rate system in which each country’s currency was pegged at a fixed rate to the dollar, which in turn was pegged to gold at $35 an ounce. This agreement officially established the dollar as the world’s reserve currency; countries began accumulating reserves of USD, which they mainly stored in U.S. treasuries. While the Bretton Woods Agreement was ultimately canceled in the early 70’s in favor of the floating exchange rates that exist to this day, the long-term effects remain, and the U.S. has since maintained a chokehold over global currency markets.

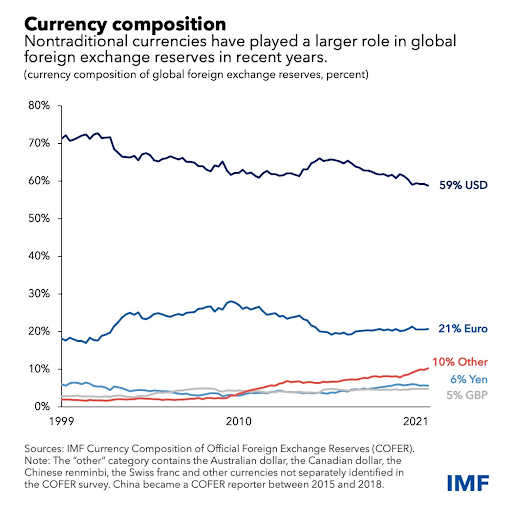

The United States Dollar currently holds 59% of all global foreign exchange reserves. While this is certainly a position of dominance, it is a steady decline from its peak in 2001 at 70%. Surprisingly enough, the decrease in dollars within exchange currency reserves did not result from an increase of other traditional reserve currencies, such as the British pound, euro, or yen. All three have stayed at relatively the same percentage of global reserves over the past couple decades.

A quarter of the shift away from the dollar can be attributed to the rise of the renminbi (RMB). China has publicly stated its intentions to internationalize the RMB by increasing its share in global transactions and central bank reserves. While the RMB hasn’t made much progress on the international scale yet, it has gradually been putting its mark on BRICS countries. BRICS –– originally founded by Brazil, Russia, India and China in 2006 as a way to challenge the economic and political dominance held by the West –– is a pipeline through which China can exert the RMB’s influence on the world. China has established bilateral swap lines with all founding BRICS members (except India) and with forty additional central banks throughout the globe. Russia, its largest partner, holds a third of global RMB reserves and exchanged more than $395 billion with the RMB in 2023, meaning that the RMB overtook the dollar as Russia’s most traded currency.

China has introduced aggressive policy measures to push the RMB as an alternative to the USD, such as its introduction of new financial infrastructure similar to the U.S.. Its Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), introduced in 2015, mirrors many aspects of the U.S. Clearing House Interbank Payments System (CHIPS) it seeks to imitate. While only possessing a fraction of worldwide transactions, it has grown 40% year over year on average and shows no signs of slowing down. Should it continue to gain traction, CIPS could position itself as a staunch alternative to the Western dominated financial transaction system.

Three quarters of the shift away from dollars can be attributed to the rise of nontraditional reserve currencies, defined as any currency besides the U.S. dollar, yen, British pound sterling, or euro. Prime examples of nontraditional currencies are the Australian and Canadian dollars, South Korean won, and Swedish krona. Worldwide holdings of nontraditional currencies currently measure $1.2 trillion USD and 10% of all reserve holdings, compared with a negligible $30 billion only 25 years ago. They currently amount for almost as much as the Japanese yen and British pound put together.

It’s also important to note gold’s rise in central bank reserves across the world. Central bank purchases of gold in 2022 were the highest ever on record, up 152% year over year. Geopolitical uncertainty, led by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and high inflation across the world, were driving forces in its increased purchasing. While this increase doesn’t play a big role in explaining the shift away from the dollar over the past few decades, it is indeed an example of central banks’ current motivation to diversify their reserves and could potentially play a larger role in the future should this level of purchasing continue.

China’s impact on the dollar’s decrease in foreign exchange reserves comes mainly as a result of their longstanding objective of challenging the U.S. as the world’s most powerful country. Weakening the dollar’s stronghold over the global economy would be a large part of achieving this goal. Its partnership with Russia in de-dollarization, as well as the influence of RMB within BRICS, can pose a serious challenge to the dollar’s dominance in the long term. Even though RMB hasn’t made inroads on global reserve shares, the mere fact that BRICS’ share of world GDP (32%) now outnumbers that of the G7 countries (30%) provides enough reason to believe the RMB could pose a long term threat to dollar dominance. While it appears very unlikely in the short term, BRICS naming RMB its official reserve currency at some point in the future would assert it as an undeniable global power.

Transcending political alliances, countries throughout the world are increasingly aware of the dollar’s punitive power. The dollar’s current importance to the global economy allows U.S. financial sanctions to be devastating as all trade performed in USD, even among independent countries, can be subject to US sanctions. The U.S. ‘ punishment of Russia as a result of the 2022 Ukraine invasion is a prime example: $300 billion of Russian central bank assets were frozen and a sovereign debt default was triggered. Russia felt these effects hard and was forced to increase their trade relationship with, and therefore dependence on, China’s RMB (ruble-RMB trade increased by eighty times between February and October of 2022).

While Russia was able to find alternatives due to its size and strength, the vast majority of countries would have no ability to protect themselves from sanctions of this kind and would be decimated. Most Western countries shouldn’t have to worry about sanctions in the short term, but even they recognize that being this dependent on a single nation’s goodwill is simply not fiscally intelligent in the long run.

US sanctions also often hit the private sector. For instance, BNP Paribas was fined $9 billion in 2014 for transacting with entities in Sudan, Iran, and Cuba, all of which were subject to U.S. sanctions. ZTE Corporation, a partially Chinese state-owned telecommunication firm, was fined $1.2 billion after shipping telecommunications equipment to North Korea and Iran. Private firms like these being subject to U.S. sanctions only increases countries’ motivation to decrease dependence on USD, since whenever the firms are fined, the host country’s economy suffers as well.

Even though the dollar’s usage as a foreign policy weapon isn’t a recent phenomenon, the extent to which sanctions have been handed out in recent years by the U.S. is certainly worrying for countries heavily dependent on USD. BRICS members counter this by increasing reserve shares of RMB and the rest of the world counters this by increasing reliance on nontraditional currencies and gold.

While the geopolitical weaponization of the dollar provides plenty of reason for countries to procure alternatives for the dollar, the advancement of financial technologies is what facilitates these changes to occur, specifically with nontraditional currencies. For one, the liquidity of markets in these currencies has increased significantly due to falling transaction costs, which have come as a result of new electronic trading platforms and foreign exchange transaction technologies. There is no longer the incentive of higher savings when trading with USD.

Central banks have also become more aggressive in their pursuit of greater returns as they are more willing to take the higher risks associated with nontraditional currencies. Although the high interest rates of the past year or two could have the potential to reverse this trend, the low rates that had become custom in America had plummeted bond yields towards zero. Banks therefore pursued higher yielding alternatives, which they found in nontraditional currencies.

Despite these threats, the U.S. has no immediate reason to worry about losing its grip over global currency markets. Its dominance will not be rivaled in the short and medium term. However, the dollar is certainly susceptible to losing its position as the singularly dominant currency in the long term. No one currency is set to replace it, instead, a combination of currencies will continue to eat away at its share until it loses its status as the world’s official reserve currency.

What stands in the RMB’s way are the strict capital controls that Beijing imposes upon it, which severely limit how much money can be freely moved in and out of the country. Central banks have a serious lack of trust both in China’s autocratic government and its transparency surrounding financial data. The country is also in the midst of an economic crisis: growth rates are falling, debt is skyrocketing (its 2023 debt-to-GDP ratio was 288%), and the housing sector is collapsing. In addition, China will need India’s cooperation in order to truly break the RMB into BRICS; India currently refuses to maintain any bilateral swap lines and is generally indifferent at best to China’s ambitions of RMB globalization.

Despite these short term struggles, the RMB looks poised to continue its implementation through BRICS, an organization which is only increasing every year (over forty countries have expressed interest in joining). Its CIPS system offers a RMB-led alternative to the Western CHIPS and Swift, which will become especially attractive should Western-Eastern tensions boil over in the wake of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, for instance. Never will the RMB reach the international status of the dollar, at least with China’s current form of government, but it will continue to gradually ease itself into world adoption through BRICS allies.

Nontraditional currencies currently pose the largest threat to the dollar’s dominance. Countries’ ambition to lessen dependence on the dollar due to its usage as a tool for foreign policy, combined with new financial technologies that facilitate transactions in these nontraditional currencies, make increasing their share in foreign reserves an increasingly attractive alternative.

Since the US only seems to be increasing their weaponization of the dollar as a tool for foreign punishment, countries around the globe will continue to push for portfolio diversification. BRICS countries will focus on RMB expansion, and the rest of the world will increase holdings of nontraditional currencies.

In the event that the U.S. loses its position as the world’s reserve currency, the effects would be catastrophic domestically. It would be forced to completely overhaul its monetary policy, especially given its recent heavy dependence on quantitative easing. This occurs when the Fed buys bonds and other securities on the open market, thus increasing the overall money supply and therefore liquidity. The U.S. would no longer be able to borrow at incredibly low rates given its reduced leverage, subsequently forcing the country to take on more expensive debt. Given the already high deficit and national debt, the U.S. would most likely have to increase taxes and print money to pay everything off, causing extreme inflation and sending the economy into a downhill spiral. This would immediately tank America’s standing as a global leader, and other countries would swoop in and fight for the opportunity to increase geopolitical power by controlling what was once the U.S.’ share of currency markets.