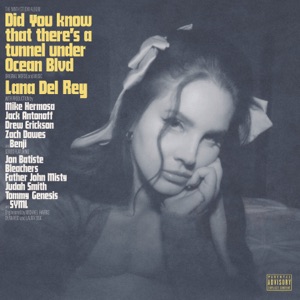

Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd: Lana Del Rey’s Melodic Rumination on Life, Death, and Beauty

Cover art for Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd pictures Lana Del Rey in a blue-toned black-and-white photo (reminiscent of old Hollywood starlets) as she gazes at the camera in rumination.

“And I’m gonna take, mine of you with me.”

So goes the sonorous refrain of the opening track to Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd, artist Lana Del Rey’s ninth studio album, an indelible work of melancholic Americana brewed on the timbre of musical strings.

It is perhaps her boldest endeavor as an artist since her 2019 album NFR!, a record met with sweeping admiration from critics, labeling her as one of the most exceptional songwriters our world has to offer.

Ocean Blvd marks a volta of thematic discography: in NFR!, living was presented as a cage unto the psyche, but her most recent album exemplifies life as an opportunity to peer into the melodramas of love & the theater of reality. Living is not a travesty of existence, but now the tool through which Del Rey frames herself.

And in Del Rey’s most recent collection of work, the flashes of poetry are as richly philosophical as ever.

The album is a spacious, poetic grasp of family, longing, and spirituality—it is the search of meaning and beauty in places where it is too often forgotten. In the words of producer Jack Antonoff, Del Rey has “reached a point in her work… where there’s really no place to go but out into the wilderness, artistically.”

And so she ventures, beginning with “The Grants,” a song that references the singer’s family name, one that reverberates with choral harmonies—as Del Rey’s pastor proclaims, “after you leave, all you take is your memories.” The album opens with an elegiac ode to how family forms a tapestry of experiences meant to be preserved even when the spirit departs from our bones.

As listeners, we are introduced to Del Rey’s exigence on Ocean Blvd—to experience all the entanglements, romances, and tragedies that form the endless movie we’ll play to ourselves in the afterlife. “The Grants” eulogizes life’s temporary, transient nature as its most worthwhile quality, as the song flourishes—”It’s a beautiful life / Remember that too for me.”

The record transitions almost seamlessly as we explore the notions of fleeting beauty with Del Rey; Ocean Blvd’s title track is a dreamy, trance-like ballad with a gradual crescendo to the grandeur of the final chorus. It’s a song that marinates in abandoned loneliness—“handmade beauty sealed up by two man-made walls,” she sings.

In this single, she’s able to craft a self-metaphor of a lonely tunnel, but this “tunnel under Ocean Blvd” is of elegance, adorned with mosaic tiles, yet sheltered off from the gaze that deserves to be shone upon it. The track is steeped with desire, desperate and raw, but it’s freckled with tragedy—the tragedy of being forgotten.

Perhaps equivalent in its immediacy, track 4 in the album, “A&W,” is an intense, foreboding song that confronts feminine maturity and the complex dichotomy of sexuality & love in the speaker’s life. The lyricism conveys an accelerated transition from innocence to adulthood—it’s a portrayal of physical relationships displacing romantic ones, painting love as colorless. The image of sexuality is compounded by the latter verses—how the media’s eyes see survivors of sexual assault as those who “ask for it.”

All of the themes addressed within “A&W”—sexuality, romance, maturity, power, the public eye—culminate with Del Rey’s own artistic mythology in the song’s final verse; here, the singer tells of “Jimmy,” a recurrent figure in her discography and a representation of an abusive partner. The single ends on an intense depiction of a toxic relationship, and confounds “A&W” as a Del Rey’s Woolf-ian stream of consciousness that offers a distinctive image of womanhood in the 21st century.

As we amble further down the tunnel, we envision evocative imagery throughout; notably, another extended-metaphor statement in the album is track 6, “Candy Necklace.” This song presents infatuation, childlike and loving, as an intoxicating force; the love interest’s reckless nature is compared to a candy-embellished necklace, an object of obsession for the speaker.

Verse 2 shifts the grandiose love to a poisonous fixation, the speaker whispers, “you’ve been bringing me down / I can see it now.” The love that was once a “white fire” is now the root of the speaker’s turmoil; the narrator is in denial, stretched thin by infatuation.

Similar themes of toxicity are addressed in “Fishtail,” a track overwhelmed with a trap-beat, synths, and mid-tempo R&B, a stark contrast to the harmonies of previous songs. In this track, Del Rey presents the metaphor of fishtail braids as a symbol of trust—specifically, fickle trust in a partner.

She sings, “Don’t you dare say, that you’ll braid my hair, babe,” in the rainy backdrops of synthwave, metaphorically expressing the onset of chaos in the speaker’s relationship—“Fishtail” is a song of pained knowledge, the knowledge that professions of love may only be told for the sake of gaining one-sided trust, not for unconditional romance. Love, as we have seen through the album so far, is often illusionary, carrying facades of meaning with beauty being buried under layers of toxicity, emotion, and obsessiveness.

And so these imperfections are explored within “Kintsugi”—a song inspired by the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by filling in the missing pieces with liquid gold; an object’s antiquity, however perilous, is an outlet of its beauty. The song is an exploration of grief & bereavement, watching loved ones recede as the heart breaks again and again until it is battered.

Yet, as Del Rey sings with subtlety—”that’s how the light gets in,” a broken heart is only made more beautiful by all its fragments.

Nearly a continuation of this motif, track 12, “Let The Light In” is a honey-droplet, gilded love song hung upon the scenery of warm guitar chords. Del Rey’s soft vocals harmonize with Father John Misty’s, amplifying the sentimentality of romance depicted in the scene of this track.

“Ooh, let the light in,” Del Rey serenades in her higher register over the orchestral strings of the instrumentals—the track questions the nature of romance, whether light should seep into our imperfections or if broken hearts should be cloaked and unseen. Perhaps love is most beautiful when its tragedies, heartbreaks, anti-glamours are not enshrouded, but treasured, Del Rey artfully prompts.

So our journey closes at the end of the tunnel, at “Taco Truck x VB,” a remixed version of a single from her 2019 album NFR! with an added verse at the beginning, a final touch to Ocean Blvd that reinforces the conceptually layered, stacking nature of her discography. The authenticity of Lana Del Rey is cyclical—her past is what informs her present artistic endeavors, and her work is iterative, neverending, and timelessly tragic.

Perhaps we are witnessing the breakthroughs of our decade’s greatest songwriter, a Sylvia-Plath broken genius of artistic expression whose work may be analyzed like classic literature after centuries of rumination. For now—we know she is, above all else, a beacon of originality in a music industry thought to be homogenous and a poet of our time.

She sings like she’s lived and loved for thousands of years.

And, in her words,

“Soundin’ off, bang bang, kiss kiss.”

Emilia S • Apr 29, 2023 at 1:48 pm

Thank you for this amazing analysis!

– A fellow Lana stan